Automatic language translation

Our website uses an automatic service to translate our content into different languages. These translations should be used as a guide only. See our Accessibility page for further information.

15 JULY 2025

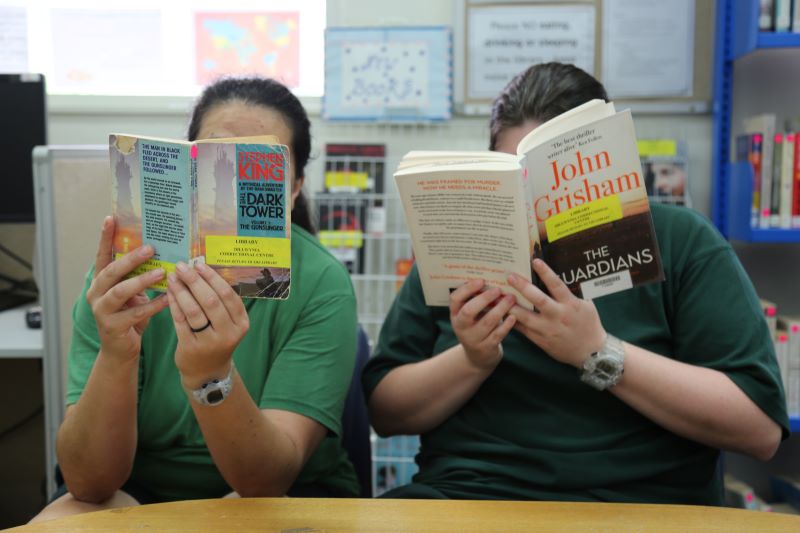

Prison libraries have a surprising past. From makeshift collections on the First Fleet to religious books ‘on loan’ in early NSW gaols, their future promises to be just as compelling. With a role in keeping inmates informed, entertained, and educated, these libraries are well-visited, well-maintained, and keep their readers well-read.

The story began in the 1830s when religious texts were provided to convicts to support reform, donated by groups like the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge.

However, even convict ships had their own ‘libraries’! Some ships transporting convicts to Australia carried books, with a person appointed to care for them, making them the first librarians in the penal colony.

In the late 1890s, Frederick Neitenstein, Chief Administrator of NSW Prisons, established libraries for officers. By 1898, Minister for Justice Charles Alfred Lee introduced official prison libraries, offering literature and technical books to help inmates build skills for release.

Today, prison libraries in NSW offer inmates a chance to improve their literacy, learn new skills, and explore different worlds. Corrective Services NSW (CSNSW) operates at least one library in each correctional centre, along with the Brush Farm Corrective Services Academy Library.

“The libraries inside the correctional centres are staffed by inmates, overseen by a library liaison officer,” explains Manager, Library Services Kim O’Grady.

“It is a popular position among the inmates, and it is important that we get the right people. They enjoy working there, it gives them some purpose, we have had inmates doing courses in library qualifications to pursue work as library assistants on their release.”

Whether it is an opportunity for inmates to learn something new or the chance to disappear to another world, the library is the only reasonable form of escape available to inmates.

“We buy about 8,000 books a year, responding to what inmates are looking for,” says Kim.

“Jack Reacher is the most popular series, along with John Grisham and Game of Thrones. Men like military history, and women enjoy mystery. We don’t allow things that could harm people, so occult and true crime are not allowed, and we look closely at some of the self-help titles.”

Remarkably Shantaram is one of the most requested books and is approved – an Australian novel about a convicted bank robber and heroin addict who escapes from Pentridge Prison in the 1980s and flees to India.

The library serves practical purposes as well, helping inmates improve literacy, study for life post-release, and access legal information. It also combines tradition with technology to help parents connect with their children.

“We have a large selection of children’s picture books in our libraries, we know inmates like to read to their children. They use the tablets for this during video calls with family. It is such a normal thing for a parent to do and it is great that we can facilitate this for them.”

In a recent initiative to expand digital access, Kim O’Grady has worked with the State Library of NSW and the Guttenberg Library to deliver thousands of e-book titles directly to inmates’ tablets. This means inmates can access a wide range of literature, supporting education and recreation in a format that’s accessible and secure.

Last updated:

We acknowledge Aboriginal people as the First Nations Peoples of NSW and pay our respects to Elders past, present, and future.

Informed by lessons of the past, Department of Communities and Justice is improving how we work with Aboriginal people and communities. We listen and learn from the knowledge, strength and resilience of Stolen Generations Survivors, Aboriginal Elders and Aboriginal communities.

You can access our apology to the Stolen Generations.