Automatic language translation

Our website uses an automatic service to translate our content into different languages. These translations should be used as a guide only. See our Accessibility page for further information.

The Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) is the main government department in NSW responsible for administering child wellbeing and safety laws under the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998 (the Care Act) and the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Regulation 2012.

When there are concerns that a child or young person is not safe in the care of their parents, an appropriate court order may be sought to keep the child safe. This will be primarily through the NSW Children's Court.

NGOs with primary case responsibility for children will also be involved at various points in the court process.

The Children’s Court should not be an adversarial process. DCJ is a model litigant in care proceedings. This means that DCJ must comply with the Model Litigant Policy. The Model Litigant Policy is designed to provide government agencies with best practice guidance in maintaining proper standards in litigation and the provision of legal services in NSW.

The role of practitioners is to be balanced and fair, and provide all available relevant information the Children’s Court needs to reach a decision.

There are also other courts that may make orders relating to children and their families including the Local Court, District Court, Family Court and Federal Circuit Court, and the Supreme Court of NSW.

DCJ and community partners will often work with families to ensure a child’s safety, welfare and wellbeing is protected. In some circumstances DCJ may need to apply to the Children’s Court for a court order when it is believed that a child or young person is in need of care and protection. This might include where DCJ considers that the child should no longer live with their parents or carers.

When a child is assessed as being at risk of significant harm, DCJ must offer alternative dispute resolution (section 37 of the Care Act) to the family before commencing care proceedings, unless it would not be appropriate to do so due to exceptional circumstances. An example is if holding alternative dispute resolution would place a participant at risk of harm due to family violence.

Care and protection proceedings are commenced by filing an application at a Children’s Court registry. The proceedings are then listed before the Children’s Court.

All parties should be served with the application, related documentation and a notice of listing advising them when and where the matter is listed before the Court. The types of applications include:

Note: An application for a care order is an initiating application when there have been no previous proceedings. An application to vary or rescind a care order can be made when a party can demonstrate to the court that there has been a significant change in relevant circumstances since the last care order was made or last varied.

The parties who have a right to appear in care and protection proceedings include: DCJ, the child or young person, and parents and any other person(s) having parental responsibility for the child or young person (section 98). Legal representatives usually appear before the court on behalf of their client. It is uncommon for children to be present at the Children’s Court.

Children will have a separate legal representative in Children’s Court proceedings who will help the Court make a decision. Children aged 12 years and over will have a direct legal representative who will act on direct instructions from the child (section 99A and 99C).

Children under 12 years will have an independent legal representative who should ensure that the child’s views are heard by the Court and that all relevant evidence is available to the Court. However they do not have to take instructions from the child (section 99A and 99B).

A person who has a genuine concern for the safety, welfare and wellbeing of a child might also ask the Children’s Court to allow them to appear in the proceedings (section 98(3)).

If you are providing services to a family or a child and there is a matter before the Children’s Court in relation to that child or family, you may be required to provide evidence to the Court about your work. The services the Court may be interested in hearing about include case management of children in out-of-home care and early intervention. Initially you may be asked to provide an affidavit, which will be provided to the Court and the other parties, and then you may be called to give evidence in person.

Once the matter is before the Children’s Court, the first step is usually the making of interim orders that will typically remain in place until final orders are made. During this time, services can continue to work with a family towards making it safe for a child to return home if possible.

The Children’s Court will need to find that the child is in need of care and protection before making final orders.

If at any stage during the proceedings everyone agrees on what final orders should be made to protect the child, final care orders can be made “by consent”, providing the judicial officer also agrees that the orders are appropriate.

If no agreement can be reached, the matter will need to be heard and determined by a judicial officer

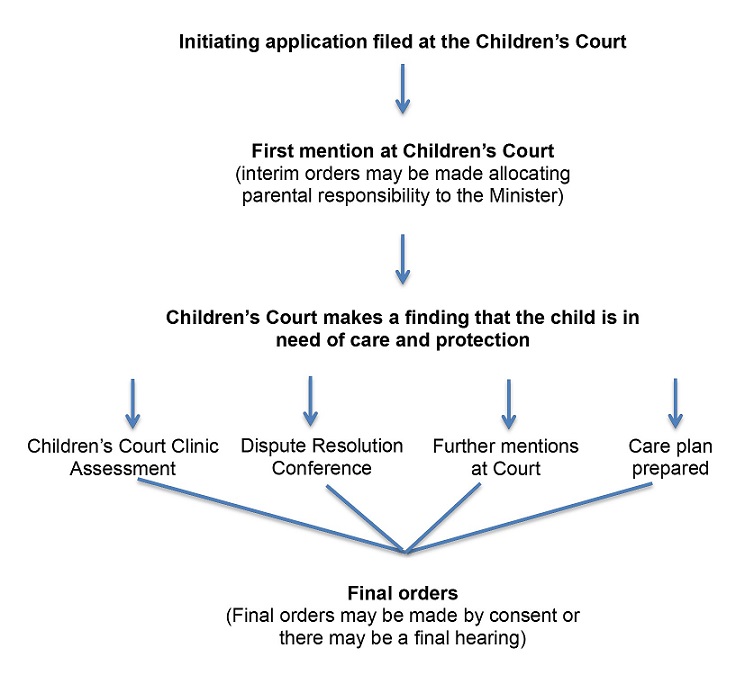

The following flow chart depicts the typical pathway for an application for a care order.

A text alternative to the Application for a Care Order diagram is available.

The Children's Court uses alternative dispute resolution (ADR) in care and protection cases, which can take the form of a dispute resolution conference (DRC). The purpose of ADR is to provide a safe environment that promotes frank and open discussion between the parties in a structured forum. This is to encourage agreement on what action should be taken in the best interests of the child or young person.

Once a care application has been filed in the Children’s Court, the Magistrate or Children’s Registrar responsible for the management of the case will determine if and when a DRC should take place. A DRC should be held as early as possible in the proceedings to facilitate the early resolution of a care application. More than one DRC may be held at different stages of the proceedings if appropriate.

This YouTube video provides information about attending a DRC.

Special support services and programs are available to assist Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders with legal problems and court matters.

The Children’s Court may make an emergency care and protection order (section 46) if it is satisfied that the child or young person is at risk of serious harm.

The emergency care and protection order places the child or young person in the care responsibility of the Secretary, or the person specified in the order.

This has effect for a maximum of 14 days and can be extended once only, for a further maximum of 14 days. This kind of order should only be sought when there is a reasonable belief that the safety issues for a child or young person are able to be resolved in the 14 day limit of the order.

The Children’s Court may make an assessment order (section 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59) for:

An assessment order authorises a person carrying out the assessment to do so in accordance with the terms of the order. A child must be informed about the reasons for the assessment in language and a manner that they can understand, having regard to their development and circumstances.

Any party to a care application may make an application to the Children’s Court for an assessment order. If granted, magistrates or judges request an assessment via the Children’s Court Clinic. The clinic will refer the matter to the most appropriate Authorised Clinician to undertake the assessment and write a report, unless the Children’s Court Clinic is unable to prepare the report, or it is of the opinion that it is more appropriate for the report to be prepared by another person.

The role of the Children's Court Clinic is to assist the Children’s Court by:

For more information on what may be included in an assessment, please see Information for those seeking an assessment.

For the purpose of an assessment, a Clinician will usually talk to the child and parent/s, and may also talk to other people involved with the family such as teachers and support services.

A supervision order (section 76) is usually made where a child or young person is assessed to be in need of care and protection but the concerns do not prevent the child from residing with their family. However close monitoring of the child is required. The order places the child or young person under the supervision of the DCJ Secretary. The maximum period a supervision order can be made for is 12 months but the Children’s Court can order a supervision order for up to 24 months, if it is satisfied that there are special circumstances.

An order accepting undertakings (section 73) is a promise to the Court given by a person responsible for the child or young person, such as their parents or carers to do or not do certain things. An undertaking must be in writing and signed by the person giving it. A Family Support Officer may be appointed to ensure that the Orders prescribed have been clearly explained and properly understood. If the Children’s Court finds that an undertaking has been breached it may make such orders as it considers appropriate in the circumstances.

A contact order (section 86) can be made that set out minimum levels of contact for a child or young person to have with their parents, relatives or other significant people. This order can also require that certain contact be supervised and who will supervise the contact. The maximum period that may be specified in a contact order is 12 months. However, if the child is subject to a guardianship order and the Children’s Court is satisfied that a contact order of longer than 12 months is in the best interests of the child, a longer order can be made.

Contact orders can be changed by agreement under a contact variation agreement signed and dated by the parties and registered with the Children’s Court (section 86A).

A prohibition order (section 90A) prohibits any person, including a parent of a child, from doing anything that could be done by the parent in carrying out their parental responsibility. If the Children’s Court determines that a prohibition order has been breached, it may make such orders as it considers appropriate in the circumstances.

Where a child or young person is in need of care and protection, the Children’s Court may make an order allocating parental responsibility (section 79), or aspects of it, to specific people, including the Minister.

The specific aspects of parental responsibility that may be allocated include, but are not limited to, the child’s:

The Children’s Court must not make an order allocating parental responsibility unless it has given particular consideration to the permanent placement principles and is satisfied that the order is in the best interests of the child or young person.

If the Court approves a permanency plan involving restoration, guardianship or adoption, the maximum period an order can be made allocating parental responsibility solely to the Minister is 24 months.

A guardianship order (section 79A) is an order made by the Children's Court that places a child under the parental responsibility of a guardian until the child turns 18.

Such orders are made in preference to long term parental responsibility to the minister where this is practicable and in the child’s best interests.

See what are guardianship orders?

See Orders in care and protection matters for further information on court orders.

The Children’s Court cannot make an order allocating parental responsibility unless it expressly finds that permanency planning for the child or young person has been appropriately and adequately addressed (section 79(3)). The permanency plan is usually part of the child’s care plan.

A permanency plan for an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child or young person should address how the plan has complied with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child and Young Person Placement Principles (section 13).

Care plans are made in consultation with the child, their family, the non-government organisation (if one has primary case responsibility), and any other people or services involved in the care planning for the child. Practitioners should work in partnership with all parties to support the common goals in relation to a child’s safety and wellbeing.

A cultural plan is a critical piece of work that must be completed as part of a care plan for children who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander or have multicultural backgrounds. This involves planning for how families, carers and services will support a child to maintain identity, community and connections to their culture. It is developed in consultation with Aboriginal children and families to ensure decisions about connection and culture are informed, and to ensure Aboriginal people play a greater role in the decisions affecting them.

See Care and Cultural Planning.

When developing a care plan, consideration must be given to what option will provide a permanent safe and nurturing home for a child. To make a decision about this, the permanent placement principles (section 10A) must be applied.

Please see Part 1 for more information on the permanent placement principles and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child and Young Person Placement Principles.

A parent responsibility contract made under section 38A is a voluntary agreement between DCJ and one or more primary carers of a child. It aims to improve the parenting skills of the carers and encourage them to take specific actions to assist them in taking greater responsibility for their child. A parent responsibility contract can be offered when DCJ has assessed that there are concerns for a child’s safety and wellbeing, and the primary carers can commit to taking realistic steps to address these.

A parent responsibility contract is not a court order, but is registered with the Children’s Court. It is time limited to periods not exceeding 12 months. It can only be entered into once within any 18 month period with the same primary carer.

This short video explains how parent responsibility contracts can be used to support parents to sustain change so they can keep their children safe at home.

Sometimes the Children’s Court will appoint a GAL to safeguard and represent the interests of a child or young person or their parent.

A GAL is usually appointed for a child or young person in special circumstances where they have special needs because of their age, disability or illness (section 100).

For parents a GAL may be appointed in circumstances where the parent has an intellectual disability or is mentally ill (section 101).

A party who is not satisfied with a final order of a Children’s Court Magistrate may appeal to the District Court against the order (section 91).

The President of the Children’s Court is a Judge of the District Court, so decisions made by the President are appealed to the Supreme Court rather than the District Court.

A party must lodge an appeal within 28 days of being notified of the final order.

When an application for a child protection order is made, you may be asked to provide information in a written report or affidavit, or give evidence to a court in person.

An affidavit is a written statement which sets out the facts in numbered paragraphs. It is sworn under oath or affirmation in the presence of a witness as a solemn declaration of truth.

An oath is a verbal promise to tell the truth made while holding the Bible. A witness may choose to swear an oath on another relevant religious text.

An affirmation is a verbal, solemn and formal declaration, which is made in place of an oath. An affirmation has the same effect as an oath but does not use a religious text.

See court resources - affidavits.

A court may require information, which could be in the form of documents or a witness to attend and provide information that is relevant to a child protection matter. This is called a subpoena, however it can also be called a ‘summons’.

Information provided in response to a subpoena helps courts to make informed decisions about children, as it provides them with relevant and available information.

Note: If you have been served with a subpoena or summons in your capacity as a practitioner or employee, speak with your manager or your organisation’s legal section for advice on how to respond.

If you are personally served with a subpoena to give evidence in court, you must comply and attend court on the date specified and provide evidence in person.

To comply with a subpoena to produce documents, you must provide the documents requested on or before the date, set out in the subpoena. Documents can include things like reports, assessments, emails, or records about a children or young person, etc.

Note: Under certain circumstances or limited grounds, it is possible to object to a subpoena. For example, if complying with a subpoena would be oppressive, or the documents requested are privileged. If you have concerns about responding to a subpoena you should seek legal advice about this.

See Subpoenas.

If you are required to give evidence in a court, the lawyers for each party may ask you questions about what you know. Generally, you will be asked questions relating to the evidence you have given in your affidavit. But there may be exceptions to this, for example where you are asked to respond to fresh evidence that has been given in court by another person, or where you voluntarily provide additional evidence outside that given in your affidavit.

Always tell the truth. It is a crime to lie in court.

The Care Act says children should be told what is happening at court in a way that they can understand. Particular attention may need to be made to uphold a child with disability’s right to express their views and be heard. They have the right to be provided with age and ability-appropriate assistance so they can participate fully in decision-making, as noted in Article Seven of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Children and young people should be given an opportunity to participate in decisions affecting their lives (see section 10). Courts can be confusing for a child (as well as adults). This participation can be encouraged through:

The Witness Assistance Service (WAS) operates statewide and provides services for victims and witnesses. Police should notify WAS if victims/witnesses require specialist and/or support services if the victims and/or witnesses are:

Last updated: